The unguarded side door: reflections on my storytelling style

Australian writer John Birmingham (of He Died With a Falafel in His Hand, and Blunt Instrument fame) asked me to write a guest post for his blog Cheeseburger Gothic. Below are reposts of John’s introduction and my article.

Comics as edumucational aid

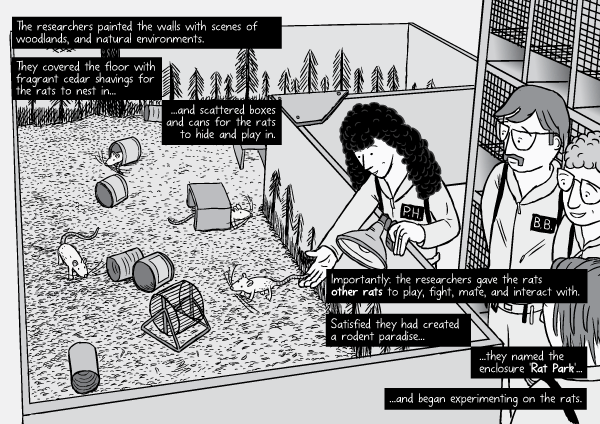

I’ve become interested recently in the rise of web comics as agit-prop tools. That videolink someone sent me explaining how people rationalise IP theft was all sorts of awesome, and Stuart McMillen’s Rat Park web comic about rethinking drug addiction is up there with it. I’ve given over the entry below to let Stuart explain the project himself. As Mr Spock would say, “Fascinating”.

Who’d have thought rats would turn to drugs to soften the harsh edges of their shitty little lives.

Stuart’s Canberra based now, having foolishly moved down there recently. Winter will sort him out, don’t you worry.

His website, www.stuartmcmillen.com has loads of free comicky goodness and acts as a billboard for his commission work. If you’re in need of some cartoon art you know where to find him now. Or you could just go check out the comix.

They’re cool.

John Birmingham

A cartooning revolution

Cartoonists like me are creating little ‘landing pads’ for readers to understand unfamiliar issues. The idea is that people read our comics without prior knowledge, become interested in a topic, and then begin their own journey of discovery.

Want to tell a mate why they should stop their chiropractic treatment? Link them to Darryl Cunningham’s Chiropractic comic. Want to explain how crazy Scientologists’ beliefs are? Link them to An Illustrated History of Scientology. Want to share what it’s like to have depression? Use Hyperbole and a Half‘s two comics to start a conversation.

Those three cartoonists and I have vastly different styles, including different levels of humour within our work. But the one thing we share is a respect for our readers.

None of us write propaganda. All of us give our readers the latitude to make up their own minds. All of us encourage our readers to learn more about the underlying topic after they have finished our comics.

A new look at addiction: Rat Park

Rat Park is my latest contribution to idiosyncratic, factual, earnest comic storytelling.

I drew Rat Park as a ‘public service’ to the internet. The comic is a form of science communication with a moral compass; a way of distilling the essence of a classic science experiment into an understandable and readable format.

What appealed to me the most is that I’m not swinging a long-held ideological battle-axe. The perspective I’m sharing in Rat Park is the result of recent research and reflection.

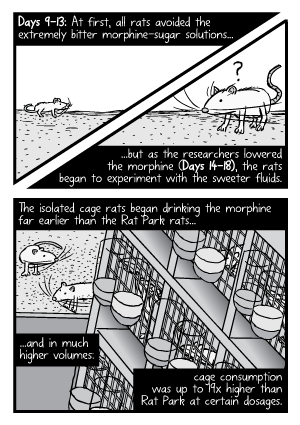

In other words, I’m sharing a new worldview to readers who likely think the same way I did, up until recently. Try heroin once, and you’ll be hooked for life…

…right?

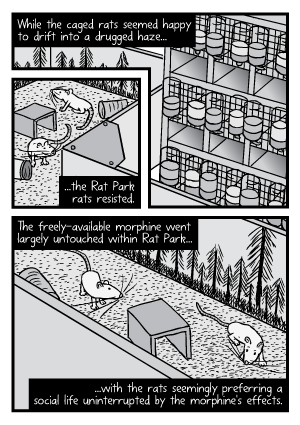

Only 12 months ago I believed this default assumption that drugs are inherently addictive. Learning about Rat Park, and Bruce Alexander’s follow-up research into human addictions challenged my view of the world.

My new little ‘landing pad’ fills an internet knowledge-gap, previously served by an incomplete and ominous-looking Wikipedia article. The comic is a 40 page primer into the science of opiate addiction. Though itself self-contained as a story, Rat Park concludes with four blog posts which elaborate on the ideas that underscore the comic.

Changing minds

Recently a bloke emailed me to say that he’d shown my War on Drugs comic to his decidedly anti-drug mother. Apparently reading my comic convinced his mum to change her mind on the drug prohibition issue!

My comic encouraged her to change her beliefs not by a full-frontal assault from the opposite side of the ideological moat. Instead, I entered through an unguarded side door, and then allowed her to draw her own conclusions with new evidence.

Rat Park is a schematic map of the way I changed my understanding of addiction. It doesn’t tell readers what I think. Instead, it shares the logic which brought me to my current conclusion.

Perhaps readers will join me; perhaps not. The decision is up to them.

Comments

Sowmya

Hi, I find this undeniably most potent and an excellent way of sharing logic.Most memorable to me...This particular Rat park shows importance of social interactions and interpersonal relationships which is needed for healthy living. Thanks for the lovely way of putting forth your thoughts!