Worm farms and identity theft

Most people think about the environmental benefits of using worms to compost household food scraps. I wanted to highlight another benefit of home composting: document destruction.

The potential for identity theft from discarded letters

Many of us are still blasé with the way we destroy mail and sensitive documents. Until recently I would simply throw unwanted mail into the recycling bin, with little concern about the potential for interception by identity thieves. I’m sure there is a lot that identity thieves could do with access to our old bank statements, bills and other pieces of correspondence. Even seemingly innocuous things such as a full name or a postal address can be pieced together into a larger jigsaw of information about a person.

Compost your sensitive documents in a worm farm

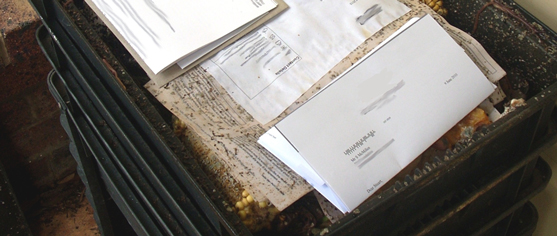

As well as destroying your documents, you will also be helping the health of your worm farm. While everyone knows that worms can eat through fruit and vegetable scraps (“nitrogen” ingredients), worms also need to be provided with drier, aged matter such as paper (“carbon” ingredients). Give the worms a balanced diet by adding your sensitive paper documents to the worm farm.

And to get the whole thing going nicely, why not pour some liquid worm castings over the paper. That ought to deter all but the most determined identity thieves! The documents will be comprehensively composted before long.

(Look at the older paper underneath the fresh letters in the above picture for an example of a document that was added less than a week ago. If you tried to peel apart the damp pages of that old lease agreement, they would tear apart in your fingers).

How I got started with worm farms

One of the most direct ways you can reduce the waste stream is to compost organic waste at your home. With around half the average household waste being organic matter (food scraps), the benefits of composting are multiple:

- households become less reliant on centralised dumps

- councils reduce the continuous expense of hauling waste in rubbish trucks.

- organic matter is steadily broken down in a controlled, small-scale fashion – rather than the anaerobic, toxic decomposition that happens in landfill.

- households create a new source of soil-enriching fertiliser, which is continuously produced for free on-site.

In the past I have used traditional compost heaps, but for the past year I have been using a commercial worm farm system. I have been very impressed by the quick and odourless way that a box filled with thousands of worms can digest its way through food scraps, compared to the slower method of compost heaping.

How worm farming works:

The worm farm is essentially a small ecosystem, needing only the input of food scraps to sustain it. The unit is split into several trays, which are snugly stacked on top of each other.

Lid removed showing the three trays of the worm farm unit

The floor of each tray contains a grid-like array of holes that allow the worms to freely migrate between the different levels of the worm farm. Typically, the worms will base themselves in the bottom layer of the unit, where they apparently spend most of their time. This is where they reproduce and lay eggs. When they become hungry, the worms will migrate to the upper layers of the unit, where their food is placed.

Each layer of food scraps becomes increasingly composted as it remains in the system. The worms will digest and re-digest the food multiple times, leaving their ‘castings’ (faeces) behind. After enough passes through the digestive system of the worm, the scraps become transformed into a rich soil high in organic matter – compost! This soil is removed from the system from the bottom tray, and the cycle continues with new matter being added to the upper trays.

Increasingly digested worm castings in the middle and bottom trays

I must mention how efficient these little decomposers are. I have had my worm farm for more than 12 months, and have continuously introduced fruit and vegetable scraps to the system. Despite the many kilograms of waste that I have fed my worms, I have not once had to remove any solid compost from the system. The only chore that is involved with operating my work farm is draining the excess liquid from the bottom of the system about once per month (there is a tap provided for this purpose). The ‘worm tea’ that comes from this tap makes an excellent fertiliser, and in fact is so concentrated that it must be heavily diluted before being applied to the garden. This worm tea contains a rich array of microbes, and is one of the best ways to add nutrients to a garden.

Draining the ‘worm tea’ from the worm farm unit’s tap

Contrary to popular conception, your worm farm will produce no odours. My system is located around three metres from the front door of my house. If I did not have the luxury of our large house and block of land, I would be happy to place the worm farm inside my house! Having said this, it is important not to add meat or dairy to the worm farm. Whilst the worms will compost meat and dairy (they are organic, after all), it will be a long and smelly process compared to the way that plant matter (fruit and veg, grains, cardboard, paper, etc) is broken down.

Besides the broader environmental, financial and societal benefits of worm farming, the entire process is also personally rewarding for the worm farmer. It is amazing to think of the volume of waste that can seemingly be reduced to zero by the biological activity of these organisms alone. The worms will digest and re-digest the food, until every possible nutrient has been unlocked and used. I see this as an analogy to the way that humanity must now look at the world; an antidote to our current ‘extract and dump’ economy. The experience of interacting with my personal ecosystem of decomposers is a fascinating and humbling experience.

In my opinion composting should be subsidised by local councils, with free composter units given to households in honour of the logistical benefits they will bring to the local sanitation department. I think that there should also be disincentives for the wasteful status quo of households putting food scraps and lawn clippings into their rubbish bins. Bin sizes should be reduced so that residents take the time to consider the bulk of material that they send ‘out of sight, out of mind’ to the dump.

Convinced? How to get started:

Home worm farm units can be purchased new for around A$80. They can be bought second-hand even cheaper. There are also many great DIY resources available on the internet that explain how to construct worm farms/compost systems from bought materials.

To start your worm farm, you will need at least 1,000 worms, which can be bought as ‘starter kits’ from hardware stores and nurseries for around AUD$30-50. Note that you must only use these ‘composting’-type species (e.g. ‘tiger worms’) in your worm farms. Other worm species, such as the common earthworm have a great place aerating the soil around the garden, but are nowhere near as quick at composting food as the ‘red wigglers’ that worm farmers use.

Occasionally worms will move from the bottom feeding tray to the liquid collector tray and are unable to return back to the surface. A good tip is to put a brick or upturned ice cream container inside this collector tray, so that the worms can easily climb out again.

Conclusion: start a worm farm

I’m seriously impressed by the amount of food that the worms have eaten through. Instead of asking for the usual round of consumer goods for your Christmas present this year, why not take a side-step and set your sights on a worm farm?

Comments